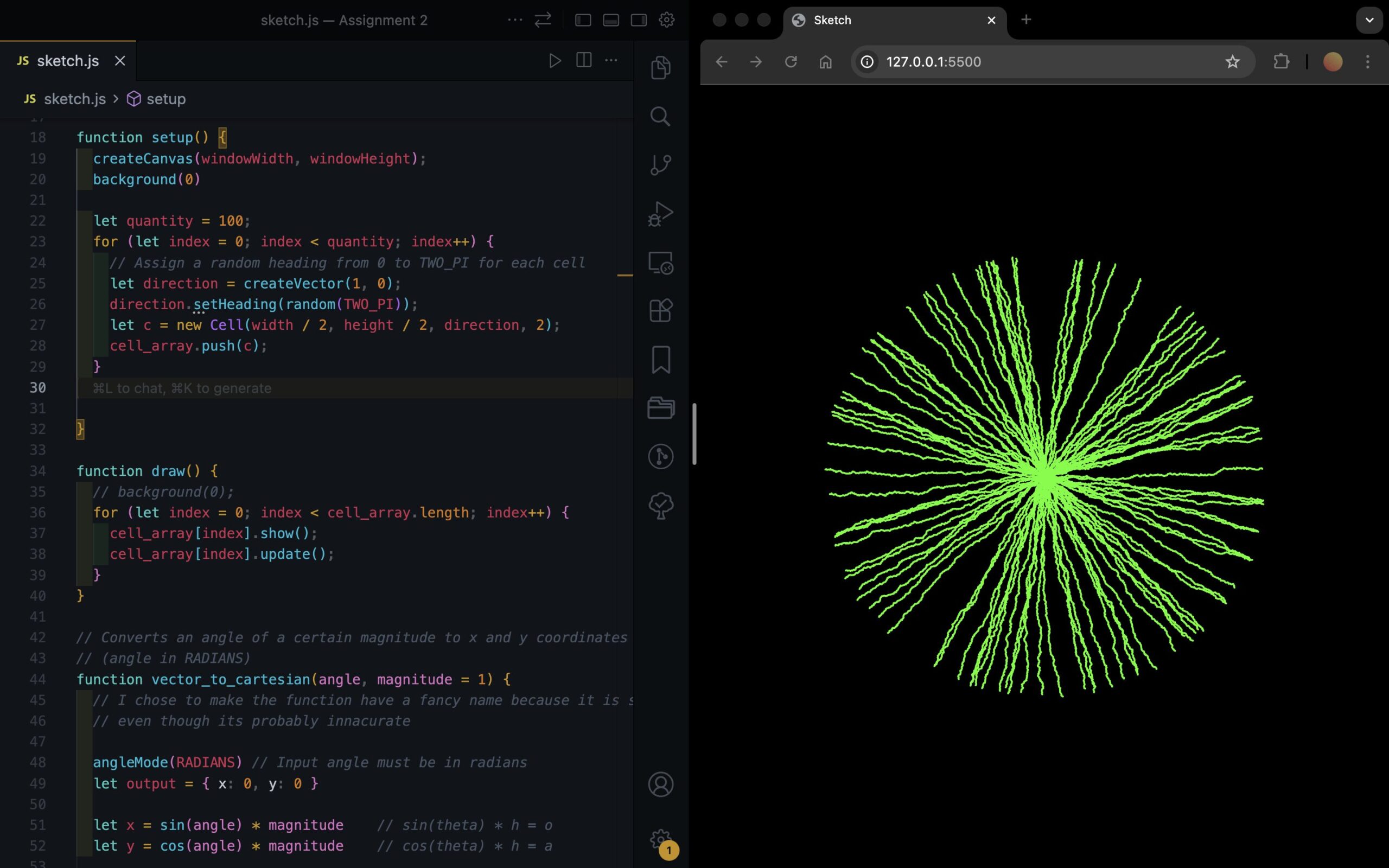

Concept and Inspiration

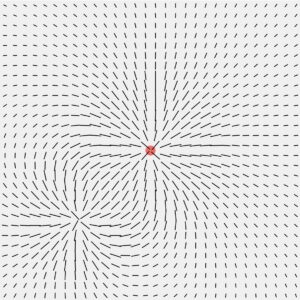

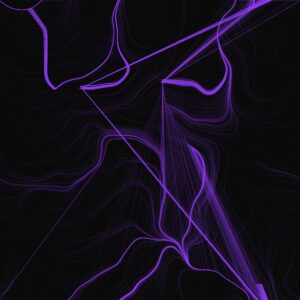

This project simulates particles moving through a maze using forces rather than bouncing off walls. Each particle is pulled toward a target point but pushed away by invisible walls shaped like rectangles. A gentle random force based on Perlin noise makes their movement look natural and smooth. I was inspired by sci-fi movies like Tron and by art that uses flowing patterns. The goal was to create flowing, energy-like paths that happen naturally from how the forces work together, not from fixed paths.

Code Organization and Naming

The code is organized into clear components: a Particle class manages position, velocity, acceleration, and trail rendering; a Wall class defines rectangular obstacles; and dedicated functions handle forces (applyGoalAttraction(), applyWallRepulsion(), and applyTurbulence()). This separation keeps the program modular and readable. Variable and function names are descriptive — like goalStrength, wallRepelStrength, and applyWallRepulsion — to make the code’s purpose immediately clear without confusion.

Code Highlights and Comments

I’m particularly proud of the wall repulsion system, which calculates the closest point on each wall rectangle to the particle and applies a smoothly scaled repulsion force. This method avoids abrupt collisions, allowing particles to gently slide away from walls rather than bouncing harshly. As a result, the particle trails form elegant, curved paths that reveal the flow of forces shaping their motion. The code is carefully commented, especially in the tricky parts like the closest-point calculation and force scaling, to clearly explain the math and logic behind this smooth, natural movement.

// push particles away from rectangles

function applyWallRepulsion(p) {

for (let w of walls) {

// find closest point on wall rectangle

let closestX = constrain(p.pos.x, w.x, w.x + w.w);

let closestY = constrain(p.pos.y, w.y, w.y + w.h);

let closestPoint = createVector(closestX, closestY);

// vector from wall to particle

let diff = p5.Vector.sub(p.pos, closestPoint);

let d = diff.mag();

// only repel if within influence distance

if (d < 40 && d > 0) {

diff.normalize();

// closer = stronger push

let strength = wallRepelStrength / d;

diff.mult(strength);

p.applyForce(diff);

}

}

}

Embedded Sketch

Milestones and Challenges

I started by making particles move toward a goal and then added trails so you could see their paths. Adding turbulence made the movement look more natural and interesting. Creating walls and figuring out how to push particles away smoothly was hard but important for realistic motion. I had to try different force strengths because if the push was too strong, particles got stuck, and if it was too weak, they went through walls. Using a semi-transparent background helped the trails build up visually, and limiting particle speed kept the motion steady.

Reflection and Future Work

This project helped me better understand how multiple forces interact to create complex, emergent movement. Compared to the simpler exercises we did in class, this system feels more full and alive because the forces come from the environment, not just between particles. It was exciting to see invisible forces made visible through the trails the particles leave. In the future, I want to add things like walls you can change with the mouse, more goals for particles to follow, moving obstacles, colors that change based on force, and sliders to adjust settings while the program runs.